So, the main ideas of the Enlightenment were:

Cult of reason and science;

Uniting mind and nature;

Belief in the transformative power of ideas and education;

Recognition of the influence of the social and natural environment on the formation of personality;

Objection to innate ideas, recognition of the advantage of experience;

Rethinking the issues of the universe and social order;

Proclamation of the "kingdom of reason";

The desire to harmonize human life with natural laws;

Affirmation of the value of an individual regardless of his social status;

Proclamation of the equality of all people (everyone has the same rights to happiness and free life);

Belief in the possibility of raising a harmonious human personality living according to the laws of reason and nature;

Affirmation of the great educational role of art in society;

The desire for a general restructuring of the world (“citizens of the world”).

“Dare to think for yourself,” wrote one of the outstanding philosophers of the Enlightenment, F. Voltaire. This idea laid the foundation for the cult of reason and science of this period. The rapid development of the natural sciences - chemistry, physics, astronomy has led to the need for not only new methodological approaches, but also a new philosophical approach to the rapidly growing amount of knowledge. The main task was to rationalize the process of cognition. At the same time, thinkers tried to determine what lies at the basis of knowledge: sensory sensations or intellect. Most philosophers, including R. Descartes (1596-1650) and B. Spinoza (1632-1677), recognized the primacy of the intellect and reason in the process of cognition, and this is how rationalism and the analytical approach in science were formed. The motto of this rationalism can be called the saying of R. Descartes “I think, therefore I exist!” The goal of human life was proclaimed to be the knowledge and acquisition of absolute truth. Moreover, science in such conditions, according to representatives of the Enlightenment, should have been completely separated from religion. In the moderate period, deism prevailed - the belief in the existence of God, who, having created the Universe, no longer interferes in its life, and in the skeptical and revolutionary periods - atheism. The positive side of this process was the liberation of the worldview of many people from superstitions and prejudices, and the negative side was the undermining of the spiritual foundations of society, which ultimately gave rise to nihilism and new social problems.

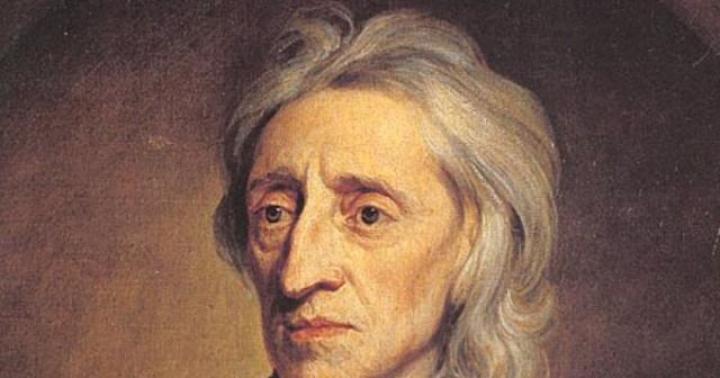

From the idea of free reason, Enlightenment philosophers came to the category of “pure” reason - a new method of thinking that would be universally suitable for all sciences and, built on the principles of reason, logic and experience, would help humanity to comprehend and subjugate nature, that is, to achieve absolute progress . The ultimate goal of this progress was declared to be the complete deliverance of humanity from troubles and suffering. But here, too, disagreements arose: supporters of empiricism (T. Hobbes (1588-1679), J. Locke (1632-1704), F. Bacon (1561-1626), D. Hume (1711-1776), D. Berkeley (1685 -1753)) considered sensory experience to be a more important component of “pure” reason, and supporters of rationalism (G. Leibniz (1646-1716), B. Spinoza, R. Descartes) considered intellect alone. But rationalism was still more popular, because objected to the presence of innate ideas. Later, they were supplemented by irrationalism (cognition through a priori methods - intuition, instinct), as well as sensationalism (cognition through sensations, feelings) and the transcendental idealism of I. Kant (1724-1804), who tried to combine both reason and experience in the theory of knowledge. In many ways, he succeeded, and thus German classical philosophy emerged, which became a bridge between the philosophy of the Enlightenment and the dialectics of the 19th century.

At the same time, solving the problem of knowledge, these philosophers, and later F. Voltaire, D. Diderot, J.J. Rousseau and others combined reason and nature, that is, they considered it not a product of the soul, but a product of matter - the activity of the human brain. The deep connection of man with nature in general was emphasized, but at the same time, the philosophy of the Enlightenment treated nature either as a chaos that should be studied and subjugated, or vice versa, as an almost rational, self-sufficient system to which a person must adapt in order to achieve harmony. This expressed one of the main contradictory aspects of “enlightenment” ideas.

Thinkers placed great hopes in resolving these contradictions in future generations, and therefore attached special importance to ideas and their transmission through education. Education and upbringing in general occupied a very important place in the research of the Enlightenment. Firstly, because thanks to them the transmission of those same ideas became possible, and secondly, because the thinkers of this era believed that each person needed to be “enlightened” separately, each individual. If the knowledge and moral development of each person progresses, then universal progress will become possible, human consciousness will be ready to accept new, fairer orders: social and legal protection of different segments of the population, religious tolerance and tolerance towards representatives of other nations, etc. The Enlightenment fought against prejudice in all its forms, as far as was possible for that time.

The issues of education were studied especially deeply by the Englishman J. Locke and the Frenchman C. Helvetius (1715-1771), who managed to deeply study the psychology of pedagogy, in particular the factors influencing the formation of personality. Among these factors, he identified social and natural prerequisites. While the latter are difficult to influence, the former require careful adjustment, that is, society itself must become better, setting an example for young people. These pedagogical theorists argued that a comprehensive intellectual, moral, physical and labor education of the younger generation is necessary. They rejected scholastic methods and proposed methods of visual education, when the student himself gains knowledge through personal experience. Great importance was attached to art as a way of education: educational classicism, educational realism and sentimentalism developed, which we will write about in more detail below. Among scientific disciplines, they noted mathematics, physics, natural subjects, and, to a lesser extent, humanities as more important. Also during the Enlightenment, joint education of boys and girls was proposed. Moreover, if J. Locke proposed abandoning religious education, especially for the poorest segments of the population, then D. Diderot completely rejected it. Much attention was also paid to the personality of the teacher, who himself was obliged to be an example of an enlightened and progressive citizen. Not all of these pedagogical theories were implemented, but they greatly changed the quality of European education.

Emphasizing the importance of social factors, the ideologists of the Enlightenment called for a radical restructuring of society, for the construction of a “kingdom of reason”, where people are equal in their natural rights, where each individual represents the highest value, regardless of gender, social and nationality. The new citizen is a “citizen of the world” - a bearer of “pure” reason, who has learned the laws of the universe and social order in a purely scientific way, and, therefore, has found freedom, harmony and happiness, both in social and personal life. Such a person is alien to egoism and prejudices (social, political, religious), he sees the good in every person, and can cooperate with everyone for the benefit of all. Later, this idea will lay the foundation for cosmopolitanism, a worldview that preaches global citizenship, when common interests are higher than private ones, incl. national. Thus, C. Montesquieu (1689-1755) and F. Voltaire developed projects for the unification of Europe, in which one can see the prototype of the modern European Union, which once again testifies to the power of influence of the Enlightenment on all subsequent historical periods. And I. Kant’s “eternal peace” with his “congress” became the prototype of modern organizations, for example the UN. At the same time, the “enlighteners” were not opponents of patriotism, but believed that it should not be fanatical, otherwise it would inevitably lead to war.

Be that as it may, all these views together gave the world rationalism in its modern world with constant dynamism, with the desire for new knowledge and achievements, for more efficiency and productivity of social life, for the development of the human personality and the improvement of social relations. At the same time, both purely pragmatic aspects stood out: the development of science and technology for the development of the economy, and idealistic ones - improving human life, achieving a state of happiness and harmony, eliminating injustice and suffering. In general, it was the Age of Enlightenment with its new ideals and values that contributed to the development of what is commonly called a market economy, although many market laws were interpreted by philosophers and economists of that time rather narrowly, only from the point of view of “mechanistic” views on supply and demand. However, all these processes were closely interconnected: industry needed a scientific and technical base, while science needed “financial” injections from business. The emergence of capital and free-thinking gave birth to new political theories and methods of their implementation, this is how the first revolutions were carried out and the first national states appeared, this is how political liberalism was born.

Along with the development of political life, economics, philosophy and science, the Enlightenment also influenced the development of artistic culture. At the same time, three main artistic movements were formed - educational classicism, educational realism and sentimentalism. The art of Rococo, closely related to Baroque, stood relatively apart.

Enlightenment classicism was different:

Rationalism;

The superiority of the general over the personal;

Harmonious construction of works;

Didacticism;

Influence of ancient heritage;

An opinion about the need to serve the whole of society, the cause of freedom and justice;

The idea of changing the existing order and establishing a more reasonable and humane one in its place;

Focusing on the conflicts that arise as a result of the clash of heroes with an imperfect society;

The problems of the works (relevant, socially significant);

The leading literary genres are tragedies, epics, odes;

Orientation towards the interests of representatives of the third estate (the entire population, except the nobility and clergy).

Representatives of educational classicism were: in “Voltairean classicism” (F. Voltaire, English poet A. Pope (1688-1744)), in “Weimar classicism” (German writers I.V. Goethe (1749-1832) and F. Schiller ( 1759-1805)), in neoclassicism (French poet A. Chenier (1762-1794), Italian poet D. Parini (1729-1799), German writer J. Paul (1763-1825)).

Enlightenment realism was characterized by:

The principle of inheritance of nature;

Truthfulness of art: concreteness, variety of facts taken from real life;

Choosing the social life of contemporaries as the main object of the image;

Studying the living conditions of people in order to determine ways to improve their existence;

The desire to generalize and analyze one’s observations, to find what is typical in the individual;

Interest in the private lives of people, their everyday life, events in their personal lives;

The predominance of novels, “philistine dramas”, “tearful comedies”;

Establishment of an active, active hero in literature;

Introduction of heroes - representatives of the third estate;

Belief in the spiritual nature of man, his creative potential, the ability to overcome difficulties and transform himself and the world;

Attention to the problem of educating a person, the formation of his character;

Idealization of heroes and didacticism of works.

Among the representatives of educational realism, the most notable personalities are D. Diderot, English writers J. Swift (1667-1745), G. Fielding (1707-1754) and R.B. Sheridan (1751-1816).

Sentimentalism came from French. the words "sentiment" - feeling and suggested:

Attention to the inner world of a person;

Exaltation of feelings, emphasizing the emotional principle;

Depiction of the life of the human heart as the main artistic principle;

Democratism of art: proclamation of the value of the human person regardless of his social status;

The presence of a philosophical basis for sentimentalism - Rousseauism (cult of feelings, human individuality and nature);

Glorifying nature - as a wise teacher of man, a mentor in matters of the heart, the embodiment of harmony and an example for inheritance;

Description of the life of ordinary people, hardworking and virtuous;

Simplicity, clarity, accessibility of style, naturalness in the depiction of life phenomena;

The predominance of stories, novels, and melodramas in literature.

Representatives of sentimentalism were: English writers L. Stern (1713-1768) and S. Richardson (1689-1761), J.J. Rousseau, Russian historian and writer M. Karamzin (1766-1826).

Rococo as a new direction in culture was characterized by:

Hedonic motives of creativity (enjoyment of life);

Narrow, chamber, intimate nature of creativity;

Focus on the tastes of the aristocracy;

Special sophistication, refinement of forms;

The brilliance and richness of artistic expression;

Aestheticism, festivity, theatricality, attention to the smallest details;

A work of art that is intended to delight and amaze the eyes, ears and imagination;

The main motives of creativity are beauty, love;

The predominance of anacreontic motifs (love, erotic plots);

Depiction of images, phenomena and events devoid of political content;

Asymmetry, inconstancy of forms and lines, spontaneity, irrationalism of creativity.

Rococo was a reaction against the excessive severity and asceticism of other cultural movements of the Enlightenment. Representatives of Rococo in Europe were the playwright from France P. Beaumarchais (1732-1799), his compatriots D. Diderot and F. Voltaire, the early I.V. Goethe and our famous compatriot M. Lomonosov (1711-1765).

It is not for nothing that we paid so much attention to the influence of the Enlightenment on artistic culture, because this also perfectly demonstrates the strength of this philosophical movement, its influence on the minds and tastes of contemporaries. On the other hand, here one can notice a very important tendency to glorify the harmony of man and nature, which is extremely important for our time, when environmental and bioethical problems have become more acute.

It is safe to say that the Age of Enlightenment contributed no less to the world cultural fund than the Renaissance. In addition, many outstanding thinkers and ideologists of the Enlightenment were, as we see, talented writers and artists. Therefore, below we will take a closer look at the views of individual representatives of the Enlightenment.

For a hundred years - from 1689 to 1789 - the world changed beyond recognition.

Enlightenment, intellectual and spiritual movement of the late 17th - early 19th centuries. in Europe and North America. It was a natural continuation of the humanism of the Renaissance and the rationalism of the early modern era, which laid the foundations of the enlightenment worldview: the rejection of a religious worldview and an appeal to reason as the only criterion for knowledge of man and society. The name was fixed after the publication of I. Kant’s article. Answer to the question: what is Enlightenment? (1784). The root word is "light", from which the term "enlightenment" is derived.

The most important representatives of the culture of the Enlightenment are: Voltaire, J.-J. Rousseau, C. Montesquieu, K.A. Helvetius, D. Diderot in France, J. Locke in Great Britain, G.E. Lessing, I.G. Herder, I.V. Goethe, f. Schiller in Germany, T. Payne, B. Franklin, T. Jefferson in the USA, N.I. Novikov, A.N. Radishchev in Russia. The Age of Enlightenment is also called by the names of great philosophers: in France - the century of Voltaire, in Germany - the century of Kant, in Russia - the century of Lomonosov and Radishchev.

The Enlightenment originated in England at the end of the 17th century. in the writings of its founder D. Locke (1632–1704) and his followers G. Bolingbroke (1678–1751), D. Addison (1672–1719), A.E. Shaftesbury (1671–1713), F. Hutcheson (1694–1747) formulated the basic concepts of the Enlightenment doctrine: “common good”, “natural man”, “natural law”, “natural religion”, “social contract”.

In the 18th century, France became the center of the educational movement. At the first stage of the French Enlightenment, the main figures were S.L. Montesquieu (1689–1755) and Voltaire/

In the second stage of the French Enlightenment, the main role was played by Diderot (1713–1784) and the encyclopedists.

The third period brought forward the figure of J.-J. Rousseau (1712–1778).

The period of the late Enlightenment (late 18th – early 19th centuries) is associated with the countries of Eastern Europe, Russia and Germany. German literature and philosophical thought gave new impetus to the Enlightenment. German enlighteners were the spiritual successors of the ideas of English and French thinkers, but in their writings they were transformed and took on a deeply national character.

In the artistic culture of the Enlightenment there was no single style of the era, a single artistic language. Various stylistic forms simultaneously existed in it: late baroque, rococo, classicism, sentimentalism, pre-romanticism. The ratio of different types of art changed. Music and literature came to the fore, and the role of theater increased. There was a change in the hierarchy of genres.

During the Age of Enlightenment, there was an unprecedented rise in the art of music. The pinnacle of the musical culture of the Enlightenment is the work of I.S. Bach (1685–1750) and V.A. Mozart (1756–1791).

The educational movement, having common basic principles, developed differently in different countries. The formation of the Enlightenment in each state was associated with its political, social and economic conditions, as well as with national characteristics.

The new natural science entails a change in the picture of the world. Empirical research of the surrounding world becomes the center of interest. Only in the 18th century did the understanding of the solar system, proposed by Copernicus in the 16th century, become generally accepted. The earth is no longer the center of the universe; a person in a new worldview becomes just a grain of sand in the Universe, but at the same time, thanks to his mind, he subjugates this Universe to himself. The Aristotelian concept of form is replaced by a mechanical-atomistic worldview: the world consists of unchanging space, things consist of particles that mechanically interact with each other. Man no longer perceives substantial forms, but only material units, which are the basic elements of the universe. The consequence of this mechanistic explanation of nature is the fundamental opposition between the finite and the infinite, between matter and spirit, the sensory and the supersensible. Thus, it departs far not only from the previous scholastic metaphysics, but also from the picture of the world in original Lutheranism (with its “ftnitum capax infmiti”). Behind this new picture of the world is the conviction in the ability of the human mind to embrace the world and master it, to establish the laws of the world order, as well as the rules of human coexistence. A rationalistic explanation of nature and a rationalistic moral teaching arise as consequences of a new attitude. The Age of Enlightenment is characterized by a naive faith in man and his capabilities.

The Age of Enlightenment took place in Europe under the sign of scientific discoveries and philosophical understanding of changes in society, which were supposed to bring freedom and equality to peoples and destroy the privileges of the Church and the aristocracy. 17th-century discoveries in the natural sciences supported the idea that reason and scientific methods could create a true picture of the world. The world and nature seemed to be organized according to strict and absolute laws. Faith in authorities has given way to consistent skepticism. The traditional class structure of society was to be replaced by a new form of state based on the power of reason and law.

The Enlightenmentists believed that every person is born free, that primitive society was the most correct. Their ideal was the kingdom of Reason. Rousseau's Social Contract is characteristic, in which he says that, having gotten rid of class, people will create a society in which everyone will limit their freedom for the sake of social harmony. The state will become the bearer of the general will.

The culture of the Enlightenment was characterized by a tendency toward rapid secularization. Natural science in a new guise contributes to an immanent explanation of the world. Secular culture grows independently of churches and denominations. The state is also freed from religious purposes and connections with Christian denominations.

The Enlightenment represents not only a historical era in the development of European culture, but also a powerful ideological movement based on the belief in the decisive role of reason and science in the knowledge of the “natural order”, corresponding to the true nature of man and society.

Enlightenment advocates advocated the equality of all before the law, the right of everyone to appeal to higher authorities, the deprivation of the Church of secular power, the inviolability of property, the humanization of criminal law, support for science and technology, freedom of the press, agrarian reform and fair taxation. The cornerstone of all Enlightenment theories was the belief in the omnipotence of reason.

The successes of the Enlightenment became possible only because another powerful social force entered the historical stage - the bourgeois class

The Age of Enlightenment was a major turning point in the spiritual development of Europe, influencing almost all areas of life. The Enlightenment expressed itself in a special state of mind, intellectual inclinations and preferences. These are, first of all, the goals and ideals of the Enlightenment - freedom, welfare and happiness of people, peace, non-violence, religious tolerance, etc., as well as the famous freethinking, a critical attitude towards authorities of all kinds, rejection of dogmas - both political and religious.

The Age of Enlightenment is characterized by the confrontation between two antagonistic styles - classicism, based on rationalism and a return to the ideals of antiquity, and romanticism, which arose as a reaction to it, professing sensuality, sentimentalism, and irrationality. Here we can add a third style - Rococo, which arose as a negation of academic classicism and Baroque. Classicism and romanticism manifested themselves in everything - from literature to painting, sculpture and architecture, and Rococo - mainly only in painting and sculpture.

Attempts to explain the behavior of the human masses by the natural and logical course of history, striving for new progressive forms of life, independent of the power of rulers, aroused the ire of reactionary circles. Many Enlightenment thinkers were harshly persecuted. Their writings were burned. But the idea of the progressive historical development of a people and its culture as factors determining the consciousness of individual individuals was strengthened and enriched in the next era, having a profound influence on research in the field of psychology.

The basis of this intellectual movement was rationalism and freethinking.

Starting in England under the influence of the scientific revolution of the 17th century, this movement spread to France, Germany, Russia and covered other European countries. The French enlighteners were especially influential, becoming “masters of thought.” Enlightenment principles formed the basis of the American Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen.

The intellectual movement of this era had a great influence on subsequent changes in the ethics and social life of Europe and America, the struggle for national independence of the American colonies of European countries, the abolition of slavery, and the formulation of human rights. In addition, it shook the authority of the aristocracy and the influence of the church on social, intellectual and cultural life.

Descartes' Discourse on Method

Actually, the term enlightenment came into the Russian language, as well as into English (The Enlightenment) and German (Zeitalter der Aufklärung) from French (siècle des lumières) and mainly refers to the philosophical movement of the 18th century. At the same time, it is not the name of a certain philosophical school, since the views of Enlightenment philosophers often differed significantly from each other and contradicted each other. Therefore, enlightenment is considered not so much a complex of ideas as a certain direction of philosophical thought. The philosophy of the Enlightenment was based on criticism of the traditional institutions, customs and morals that existed at that time.

There is no consensus regarding the dating of this ideological era. Some historians attribute its beginning to the end of the 17th century, others - to the middle of the 18th century. The foundations of rationalism were laid by Descartes in his work “Discourse on Method” (1637). The end of the Enlightenment is often associated with the death of Voltaire (1778) or the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars (1800-1815). At the same time, there is an opinion about linking the boundaries of the Enlightenment era to two revolutions: the “Glorious Revolution” in England (1688) and the Great French Revolution (1789).

- 1 Essence

- 2 Periodization according to G. May

- 3 Religion and morality

- 3.1 Dissolution of the Society of Jesus

- 4 Historical significance

- 5 See also

- 6 Notes

- 7 Bibliography

- 8 Links

- 9 Literature

Essence

During the Enlightenment, there was a rejection of the religious worldview and an appeal to reason as the only criterion for knowledge of man and society. For the first time in history, the question of the practical use of scientific achievements in the interests of social development was raised.

Scientists of a new type sought to disseminate knowledge and popularize it. Knowledge should no longer be the exclusive possession of a few initiated and privileged, but should be accessible to all and of practical use. It becomes the subject of public communication and public debate. Even those who had traditionally been excluded from studies - women - could now take part in them. There were even special publications designed for them, for example, in 1737, the book “Newtonianism for Ladies” by Francesco Algarotti. It is characteristic how David Hume begins his essay on history (1741):

There is nothing that I would recommend to my readers more seriously than the study of history, for this activity is better suited than others to both their sex and education - much more instructive than their usual books for amusement, and more interesting than the serious works that can be found in their closet. Original text (English)

There is nothing which I would recommend more earnestly to my female readers than the study of history, as an occupation, of all others, the best suited both to their sex and education, much more instructive than their ordinary books of amusement, and more entertaining than those serious compositions, which are usually to be found in their closets.

- “Essay of the study of history” (1741).

The culmination of this desire to popularize knowledge was the publication of Diderot et al. "Encyclopedia" (1751-1780) in 35 volumes. It was the most successful and significant “project” of the century. This work brought together all the knowledge accumulated by humanity up to that time. he clearly explained all aspects of the world, life, society, sciences, crafts and technology, everyday things. And this encyclopedia was not the only one of its kind. Others preceded her, but only the French one became so famous. Thus, in England, Ephraim Chambers published a two-volume “Cyclopedia” in 1728 (in Greek, “circular education”, the words “-pedia” and “pedagogy” are the same root). In Germany in 1731-1754, Johan Zedler published the “Great Universal Lexicon” (Großes Universal-Lexicon) in 68 volumes. It was the largest encyclopedia of the 18th century. it had 284,000 keywords. By comparison: in the French “Encyclopedia” there were 70,000 of them. But, firstly, it became more famous, and already among its contemporaries, because it was written by the most famous people of its time, and this was known to everyone, while over the German Many unknown authors worked on the lexicon. Secondly: her articles were more controversial, polemical, open to the spirit of the times, partly revolutionary; they were crossed out by censorship, there were persecutions. Thirdly: at that time the international scientific language was already French, not German.

Simultaneously with general encyclopedias, special encyclopedias also appeared for various individual sciences, which then grew into a separate genre of literature.

Latin has ceased to be a scientific language. In its place comes the French language. Ordinary literature, non-scientific, was written in national languages. A big debate about languages flared up among scientists at that time: whether modern languages could displace Latin. On this topic, and in general on the issue of superiority between antiquity and modernity, Jonathan Swift, the famous educator and author of Gulliver's Travels, wrote, for example, a satirical story “The Battle of the Books,” published in 1704. With the parable of the spider and the bee contained in this story, he perfectly and wittily expressed the essence of the dispute between supporters of ancient and modern literature.

The main aspiration of the era was to find, through the activity of the human mind, the natural principles of human life (natural religion, natural law, the natural order of the economic life of the physiocrats, etc.). From the point of view of such reasonable and natural principles, all historically established and actually existing forms and relations (positive religion, positive law, etc.) were criticized.

Periodization according to G. May

There are many contradictions in the views of thinkers of this era. The American historian Henry F. May identified four phases in the development of philosophy of this period, each of which to some extent denied the previous one.

The first was the moderate or rational Enlightenment phase, associated with the influence of Newton and Locke. It is characterized by religious compromise and the perception of the Universe as an orderly and balanced structure. This phase of the Enlightenment is a natural continuation of the humanism of the 14th-15th centuries as a purely secular cultural movement, characterized, moreover, by individualism and a critical attitude towards traditions. But the Age of Enlightenment is separated from the Age of Humanism by the period of religious reformation and Catholic reaction, when theological and ecclesiastical principles again took precedence in the life of Western Europe. The Enlightenment is a continuation of the traditions not only of humanism, but also of advanced Protestantism and rationalistic sectarianism of the 16th and 17th centuries, from which it inherited the ideas of political freedom and freedom of conscience. Like humanism and Protestantism, the Enlightenment in different countries acquired a local and national character. The transition from the ideas of the Reformation era to the ideas of the Enlightenment era is most conveniently observed in England at the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th centuries, when deism developed, which was to a certain extent the completion of the religious evolution of the Reformation era and the beginning of the so-called “natural religion”, which was preached by the enlighteners of the 18th century. V. There was a perception of God as the Great Architect who rested from his labors on the seventh day. He gave people two books - the Bible and the book of nature. Thus, along with the caste of priests, a caste of scientists comes forward.

The parallelism of spiritual and secular culture in France gradually led to the discrediting of the former for hypocrisy and fanaticism. This phase of the Enlightenment is called skeptical and is associated with the names of Voltaire, Holbach and Hume. For them, the only source of our knowledge is the unprejudiced mind. There are other connections with this term, such as: enlighteners, enlightenment literature, enlightened (or enlightenment) absolutism. The expression “philosophy of the 18th century” is used as a synonym for this phase of the Enlightenment.

The skeptical phase was followed by a revolutionary phase, associated in France with the name of Rousseau, and in America with Paine and Jefferson. Characteristic representatives of the last phase of the Enlightenment, which became widespread in the 19th century, are philosophers such as Thomas Reed and Francis Hutcheson, who returned to moderate views, respect for morality, law and order. This phase is called didactic.

Religion and Morality

A characteristic educational idea is the denial of any divine revelation, this especially affected Christianity, which is considered the primary source of errors and superstitions. As a result, the choice fell on deism (God exists, but he only created the World and then does not interfere with anything) as a natural religion identified with morality. Not taking into account the materialistic and atheistic beliefs of some thinkers of this era, such as Diderot, most of the enlighteners were followers of deism, who through scientific arguments tried to prove the existence of God and His creation of the universe.

During the Enlightenment, the universe was viewed as an amazing machine that was an efficient cause rather than a final one. God, after the creation of the universe, does not interfere in its further development and world history, and man at the end of the path will neither be condemned nor rewarded by Him for his deeds. The guide for people in their moral behavior is laicism, the transformation of religion into natural morality, the commandments of which are the same for everyone. The new concept of tolerance does not exclude the possibility of practicing other religions only in private life and not in public life.

Dissolution of the Society of Jesus

The attitude of the Enlightenment to the Christian religion and its connection with civil power was not the same everywhere. If in England the struggle against absolute monarchy had already been partially resolved thanks to the Bill of Rights of 1689, which officially put an end to religious persecution and pushed faith into the subjective-individual sphere, then in continental Europe the Enlightenment retained a strong hostility towards the Catholic Church. States began to take a position of independence of domestic politics from the influence of the papacy, as well as increasingly limiting the autonomy of the curia in church matters.

The Jesuits, implacable defenders of papal authority, against the backdrop of growing conflict between church and state, as well as public opinion calling for the destruction of the order, were expelled from almost all European countries. In 1759 they were driven out of Portugal, followed by France (1762) and Spain (1769). In 1773, Pope Clement XIV published the bull Dominus ac Redemptor, in which he decreed the dissolution of the Society of Jesus. All of the order's property was confiscated and, most of it, was used to create public places controlled by the state. However, the Jesuits did not completely disappear from Europe, since in Russia Catherine the Great, although very close to the idea of the Enlightenment, refused to publish the papal breve about the dissolution.

Historical meaning

Portrait of Voltaire from the palace of the Prussian king Frederick the Great of Sansoussi. Engraving by P. BakuPan-European significance in the 18th century. received French educational literature in the person of Voltaire, Montesquieu, Rousseau, Diderot and other writers. Their common feature is the dominance of rationalism, which directed its criticism in France to issues of a political and social nature, while the German enlighteners of this era were more concerned with resolving religious and moral issues.

Under the influence of the ideas of enlightenment, reforms were undertaken that were supposed to rebuild all public life (enlightened absolutism). But the most significant consequences of the ideas of the Enlightenment were the American Revolution and the French Revolution.

At the beginning of the 19th century. Enlightenment provoked a reaction against itself, which, on the one hand, was a return to the old theological worldview, on the other, an appeal to the study of historical activity, which was greatly neglected by the ideologists of the 18th century. Already in the 18th century, attempts were made to determine the basic nature of enlightenment. Of these attempts, the most remarkable belongs to Kant (Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?, 1784). Enlightenment is not the replacement of some dogmatic ideas with other dogmatic ideas, but independent thinking. In this sense, Kant contrasted enlightenment with enlightenment and declared that it was simply the freedom to use one’s own intellect.

Modern European philosophical and political thought, such as liberalism, largely derives from the Enlightenment. Philosophers of our day consider the main virtues of the Enlightenment to be a strict geometric order of thinking, reductionism and rationalism, contrasting them with emotionality and irrationalism. In this respect, liberalism owes its philosophical basis and critical attitude towards intolerance and prejudice to the Enlightenment. Famous philosophers who hold similar views include Berlin and Habermas.

The ideas of the Enlightenment also underlie political freedoms and democracy as the basic values of modern society, as well as the organization of the state as a self-governing republic, religious tolerance, market mechanisms, capitalism, and the scientific method. Since the Age of Enlightenment, thinkers have insisted on their right to seek the truth, whatever it may be and whatever it may threaten social foundations, without being threatened with being punished “for the Truth.”

After World War II, with the birth of postmodernism, certain features of modern philosophy and science came to be seen as shortcomings: overspecialization, inattention to tradition, unpredictability and the danger of unintended consequences, and an unrealistic assessment and romanticization of Enlightenment figures. Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno even believe that the Enlightenment indirectly gave rise to totalitarianism.

see also

- American Enlightenment

- Russian Enlightenment

- Scottish Enlightenment

- Thomas Abt (1738-1766), Germany, philosopher and mathematician.

- Marquis de Sade (1740 - 1814), France, philosopher, founder of the doctrine of absolute freedom - libertinism.

- Jean le Rond d'Alembert (1717-1783), France, mathematician and physician, one of the editors of the French Encyclopedia

- Balthasar Becker (1634-1698), Dutch, key figure of the early Enlightenment. in his book De Philosophia Cartesiana (1668), he separated theology and philosophy and argued that Nature can no more be understood from Scripture than theological truth can be deduced from the laws of Nature.

- Pierre Bayle (1647-1706), France, literary critic. He was one of the first to advocate religious tolerance.

- Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794), Italy. He gained wide fame thanks to his essay On Crimes and Punishments (1764).

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), Germany, composer.

- George Berkeley (1685-1753), England, philosopher and church leader.

- Justus Henning Böhmer (1674-1749), Germany, lawyer and church reformer.

- James Boswell (1740-1795), Scotland, writer.

- Leclerc de Buffon (1707-1788), France, naturalist, author of L’Histoire Naturelle.

- Edmund Burke (1729-1797), Irish politician and philosopher, one of the early founders of pragmatism.

- James Burnet (1714-1799), Scotland, lawyer and philosopher, one of the founders of linguistics.

- Marquis de Condorcet (1743-1794), French, mathematician and philosopher.

- Ekaterina Dashkova (1743-1810), Russia, writer, president of the Russian Academy

- Denis Diderot (1713-1784), France, writer and philosopher, founder of the Encyclopedia.

- French encyclopedists

- Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), USA, scientist and philosopher, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and authors of the Declaration of Independence.

- Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle (1657-1757), France, scientist and science writer.

- Victor D'Upay (1746-1818), France, writer and philosopher, author of the term communism.

- Edward Gibbon (1737-1794), England, historian, author of the History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), Germany, poet, philosopher and natural scientist.

- Olympe de Gouges (1748-1793), France, writer and politician, author of the “Declaration of the Rights of Woman and Citizen” (1791), which laid the foundations of feminism.

- Joseph Haydn (1732-1809), Germany, composer.

- Claude Adrien Helvetius (1715-1771), France, philosopher and writer.

- Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803), Germany, philosopher, theologian and linguist.

- Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), England, philosopher, author of Leviathan, a book that laid the foundations of political philosophy.

- Paul Henri Holbach (1723-1789), France, encyclopedist philosopher, was one of the first to declare himself an atheist.

- Robert Hooke (1635-1703), England, experimental naturalist.

- David Hume (1711-1776), Scottish philosopher, economist.

- Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), USA, philosopher and politician, one of the founding fathers of the United States and authors of the Declaration of Independence, defender of the “right of revolution.”

- Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos (1744-1811), Spanish lawyer and politician.

- Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), Germany, philosopher and natural scientist.

- Hugo Kollontai (1750-1812), Poland, theologian and philosopher, one of the authors of the Polish constitution of 1791.

- Ignacy Krasicki (1735-1801), Poland, poet and church leader.

- Antoine Lavoisier (1743-1794), France, naturalist, one of the founders of modern chemistry and authors of the Lomonosov-Lavoisier law.

- Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716), Germany, mathematician, philosopher and lawyer.

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781), Germany, playwright, critic and philosopher, creator of the German theater.

- Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), Swedish, botanist and zoologist.

- John Locke (1632-1704), England, philosopher and politician.

- Peter I (1672-1725), Russia, tsar-reformer.

- Feofan Prokopovich (1681-1736), Russia, church leader and writer.

- Antioch Cantemir (1708-1744), Russia, writer and diplomat.

- Vasily Tatishchev (1686-1750), Russia, historian, geographer, economist and statesman.

- Fyodor Volkov (1729-1763), Russia, actor, founder of the Russian theater.

- Alexander Sumarokov (1717-1777), Russia, poet and playwright.

- Mikhailo Lomonosov (1711-1765), Russia, naturalist and poet, one of the authors of the Lomonosov-Lavoisier law.

- Ivan Dmitrevsky (1736-1821), Russia, actor and playwright.

- Ivan Shuvalov (1727-1797), Russia, statesman and philanthropist.

- Catherine II (1729-1796), Russia, empress, philanthropist and writer.

- Alexander Radishchev (1749-1802), Russia, writer and philosopher.

- Mikhail Shcherbatov (1733-1790), Russia, historian and publicist.

- Ivan Betskoy (1704-1795), Russia, statesman.

- Plato (Levshin) (1737-1812), Russia, church leader and church historian.

- Denis Fonvizin (1745-1792), Russia, writer.

- Vladislav Ozerov (1769-1816), Russia, poet and playwright.

- Yakov Knyazhnin (1742-1791), Russia, writer and playwright.

- Gabriel Derzhavin (1743-1816), Russia, poet and statesman.

- Nikolai Sheremetev (1751-1809), Russia, philanthropist.

- Christlieb Feldstrauch (1734–1799), Russia, Germany, teacher, philosopher. Author of Observations on the Human Spirit and Its Relation to the World

- Sebastian José Pombal (1699-1782), Portuguese, statesman.

- Benito Feijoo (1676-1764), Spain, church leader.

- Charles Louis Montesquieu (1689-1755), France, philosopher and jurist, one of the authors of the theory of separation of powers.

- Leandro Fernandez de Moratin (1760-1828), Spain, playwright and translator.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), Germany, composer.

- Isaac Newton (1643-1727), England, mathematician and natural scientist.

- Nikolai Novikov (1744-1818), Russia, writer and philanthropist.

- Dositej Obradović (1742-1811), Serbia, writer, philosopher and linguist.

- Thomas Paine (1737-1809), USA, writer, critic of the Bible.

- François Koehne (1694-1774), France, economist and physician.

- Thomas Reid (1710-1796), Scotland, ecclesiastical leader and philosopher.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), France, writer and political philosopher, author of the idea of the “social contract”.

- Adam Smith (1723-1790), Scotland, economist and philosopher, author of the famous book An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.

- Baruch Spinoza (1632-1672), Holland, philosopher.

- Emmanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), Swedish, theologian and naturalist.

- Alexis Tocqueville (1805-1859), French historian and political activist.

- Voltaire (1694-1778), France, writer and philosopher, critic of state religion.

- Adam Weishaupt (1748-1830), Germany, lawyer, founder of the secret society of the Illuminati.

- John Wilkes (1725-1797), England, publicist and politician.

- Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), Germany, art critic.

- Christian von Wolf (1679-1754), Germany, philosopher, lawyer and mathematician.

- Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797), England, writer, philosopher and feminist.

Notes

- Hackett, Louis. The age of Enlightenment (1992). Archived from the original on February 9, 2012.

- Hooker, Richard. The European Enlightenment(unavailable link - history) (1996). Archived from the original on August 29, 2006.

- Frost, Martin. The age of Enlightenment (2008). Retrieved January 18, 2008. Archived from the original on February 9, 2012.

- "Essay of the study of history" (1741).

- Stollberg-Rilinger (2010), p. 187.

- Quoted from: G. Gunn. Early American Writing. Introduction. Penguin Books USA Inc., New York, 1994. Pp.xxxvii-xxxviii.

- Blissett, Luther. Anarchist Integralism: Aesthetics, Politics and the Après-Garde (1997). Retrieved January 18, 2008. Archived from the original on February 9, 2012.

Bibliography

- Gettner, “History of General Literature of the 18th Century”;

- Laurent, “La philosophie du XVIII siècle et le christianisme”;

- Lanfrey, “L"église et la philosophie du XVIII siècle”;

- Stephen, “History of English thought in the XVIII century”;

- Biedermann, "Deutschlands geistige, sittliche und gesellige Zustände"

Links

- Article in the Krugosvet encyclopedia

- Dlugach T. B. Philosophy of Enlightenment (video lectures)

Literature

- Ogurtsov A.P. Philosophy of science of the Enlightenment. - M.: Institute of Philosophy of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 1993. - 213 p.

- M. Horkheimer, T. W. Adorno. The concept of enlightenment // Horkheimer M., Adorno T. V. Dialectics of enlightenment. Philosophical fragments. M., St. Petersburg, 1997, p. 16-60

- D. Ricuperati. Man of Enlightenment // World of Enlightenment. Historical Dictionary. M., 2003, p. 15-29.

| History of Europe | |

|---|---|

| Prehistoric period |

Stone Age Neolithic Copper Age Bronze Age Iron Age |

| Antiquity |

Classical Greece Roman Republic Hellenism Roman Empire Late Antiquity Early Christianity Crisis of the Roman Empire 3rd century Fall of the Western Roman Empire |

| Middle Ages |

Early Middle Ages Great Migration of Peoples Byzantine Empire Christianity Old Russian State High Middle Ages Holy Roman Empire Crusades Feudalism Late Middle Ages Hundred Years' War Renaissance |

| New time |

Reformation Great geographical discoveries Baroque Thirty Years' War Period of absolutism Old Order Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Dutch Republic Habsburg Monarchy Empires (Ottoman Portuguese Spanish Swedish British Russian) European miracle French Revolution Napoleonic Wars Romantic nationalism Revolutions of 1848-1849 Industrialization First World War |

| Modern times |

October Revolution Interwar period Second World War Cold War European integration |

| see also |

Genetic history of Europe Military history of Europe History of European art Maritime history of Europe History of the European Union |

what is the era of enlightenment, the era of enlightenment, the era of enlightenment in Western Europe, the era of enlightenment in Russia, the era of enlightenment is

Age of Enlightenment Information About

The Age of Enlightenment is one of the most important periods not only in European history, but also in world culture. Her first ideas originated in

England and immediately spread to France, Germany, Russia and other European countries. Most historians date this ideological era to the end of the 17th and beginning of the 19th centuries, but the time of manifestation of its thoughts in different countries and fields of science and art varies.

Representatives of the Enlightenment

In the 18th century, such writers and philosophers as Voltaire, Diderot, Rousseau, Montesquieu and other cultural figures became prominent representatives of French educational literature. Their works were aimed at issues of a socio-political nature and received pan-European significance. German philosophers of the Enlightenment, such as Kant and Nietzsche, worked to solve moral and religious problems. In England, Locke, Berkeley and Hume developed the ideas of spiritualism, deism and skepticism. The American Age of Enlightenment was very different from the European Age. The actions of America's educators were aimed at fighting the English colonies and breaking with England in general.

Principles of the Age of Enlightenment

Despite some differences in views, the Age of Enlightenment as a whole

was aimed at understanding the natural principles of human life (law, religion, etc.). All existing relationships and forms were subject to criticism from the point of view of a natural and reasonable beginning. Much attention was paid to morality, education and pedagogy, in which the ideals of humanity were preached. The question of human dignity has taken on acute forms.

Signs of the era

There are three main features of the Age of Enlightenment:

1. The theory of equality of all before humanity and the law. People are born equal in their rights, the satisfaction of their individual interests and needs is aimed at establishing fair and reasonable forms of coexistence.

2. Superiority of the mind. Based on scientific achievements, the idea has developed that society and the Universe obey reasonable and logical laws, all the mysteries of the universe have been solved, and the dissemination of knowledge can get rid of all social problems.

3. Historically optimistic attitude. The Age of Enlightenment was built on the belief in the possibility of changing humanity for the better and transforming socio-political foundations in a “rational” way.

conclusions

As the Age of Enlightenment showed, the philosophy of this period greatly influenced the development of further theories about aspects of human life. His ideas formed the basis of democracy and political freedom as the basic values of modern society. Liberalism, being a modern socio-political movement, arose on the basis of Enlightenment theories. The American Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen are based on Enlightenment principles. However, the principles of the Enlightenment did not escape criticism. With the advent of postmodernism, certain aspects of philosophy began to be perceived as deficiencies. The activities of the educators seemed unrealistic. Inattention to tradition and excessive specialization were condemned.

The special place of this era, covering the end of the 17th-18th centuries, was reflected in the epithets it received: “The Age of Reason”, “ The Age of Enlightenment." The term "Enlightenment" reflects the spirit of this time, the goal of which was to replace religious or political authorities with ones based on the demands of human reason. Saying that the new era did not prescribe a dogmatic point of view for man, the researchers note that the people of the Enlightenment “...felt as a person recovering after a long illness, or a prisoner released from prison,” would feel (A. Yakimovich).

Chronologically, the Age of Enlightenment is defined as the century between the Glorious Revolution in England (1689) and the French Revolution (1789). It was an era that began with one revolution and ended with three: industrial - in England, political - in France, philosophical and aesthetic - in Germany. Over the course of a hundred years, the world has changed: the remnants of feudalism have evaporated more and more, and bourgeois relations, which were finally established after the Great French Revolution, are making themselves known more and more loudly.

The 18th century also prepared the way for the dominance of bourgeois culture. The old, feudal ideology was replaced by the time of philosophers, sociologists, economists, and writers of the new age of Enlightenment.

The sources of the new cultural era were:

Renaissance humanism;

Descartes' rationalism;

Scientific achievements of the 17th century;

Locke's political philosophy (the theory of “natural law”);

Skepticism towards religion (from the Renaissance);

Renaissance appeal to antiquity;

Early bourgeois individualism (from the Northern Renaissance);

Ideas of freedom of conscience (from the Reformation).

Characteristic features of the ideology of the Enlightenment.

1. Creation of a new sociocultural myth– a myth about a bright soul, a harmonious spirit, the power of reason and the power of reasonable morality. This myth was built and realized in polemics with the “dark forces” of the historical past, as well as religious or traditional worldview. Confrontation with the past (which was assessed as “stupidity, Christianity and ignorance”), the struggle between light and darkness became the idea of a new era of Enlightenment. In this term, the enlighteners themselves saw primarily not the idea of education, but the idea of light dispelling darkness.

Having put forward the idea of personality formation, enlighteners showed that a person has intelligence, spiritual and physical strength. The Renaissance ideal of a free personality acquired the attribute of universality and responsibility: the man of the Enlightenment thought not only about himself, but also about others, about his place in society. The focus of educators is the problem of the best social order. The Enlighteners believed in the possibility of building a harmonious society. Profound changes in the socio-political and spiritual life of Europe associated with the emergence and development of bourgeois economic relations determined the main dominants of the culture of the 18th century.

2. Change in religious worldview.

Religion in the form in which the church presented it seemed to the atheist educators to be the enemy of man.

The article “Population” in the famous French “Encyclopedia” by D. Diderot and J. d'Alembert began like this: “The goal of Christianity is not to populate the earth; his true goal is to populate the sky...”, and further the authors argued that nature overpowers all dogmatic religious attitudes. And in 1749, A. Buffon published “Natural History”, where the development of life on earth is outlined without mentioning God.

Basically, educators expressed ideas deism(from Latin - “God”) - a form of faith that arose during the Enlightenment and recognizes that although God exists in the world as its first cause, after the creation of the world, the movement of the universe takes place without his participation. God turned into a force that only brought a certain order to the eternally existing matter. During the Enlightenment, the idea of God as a great mechanic and of the world as a huge mechanism became especially popular.

Enlighteners called for the separation of faith from the church, spoke out against the church and religious fanaticism: “Crush the reptile!” Voltaire said about the Catholic Church.

The idea of religious tolerance and spiritual freedom was formulated for the first time in the history of Western European culture during the Enlightenment. A striking example is the answer of the Prussian King Frederick II (an admirer of Voltaire) to a question about religious policy: “All religions are equal and good, if only the people who profess them are honest and decent; and if the Turks and pagans come and want to populate the country, then we will build mosques and sanctuaries for them.”

3. “Discovery” of world culture and the idea of cosmopolitanism.

The Age of Enlightenment marks the emergence of interest and the beginning of the study of world culture, i.e. everything that was outside Western Europe. One of the features of the era was the idealization of antiquity. The Enlightenment created and put into circulation a beautiful myth that the history of people of different times and nations demonstrates their tendency towards tolerance and freedom.

Examples are given of pagans whose religion was crude and primitive, but did not turn them into fanatics. Voltaire begins his Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations with praise for the virtues of Indian and Chinese culture. Throughout the 18th century. works of fiction, travel notes and philosophical works, stories about “good savages” and “wise infidels” were created. Examples include the works of de Boulainvilliers “The Life of Muhammad”, W. Temple “An Essay on Heroic Virtue”, D. Maran “Conversations of a Philosopher with a Hermit” on the wisdom of the East, Montesquieu “Persian Letters”, a major study of Confucianism published by the Jesuit Order. In these works, overseas cultures, morals and religions were viewed with sympathy, and in this sympathy there was an indirect reproach to European customs and laws: against the background of the rest of the world, European society and Christian culture looked absurd and a deviation from world history. For example, David Hume argued that anger, intolerance and religious fury came into the world with Christianity.

4. The scientific spirit of the era.

In philosophy, the Enlightenment opposed all metaphysics (the science of supersensible principles and principles of being). It contributed to the development of any kind of rationalism, which recognizes reason as the basis of human cognition and behavior. In science, this led to the development of natural science, the achievements of which were often used to justify the scientific legitimacy of views and faith in progress.

A characteristic feature of the era was the fact that the generally recognized leadership in society was no longer held by artists, as was the case in the Renaissance, but by scientists and philosophers. Suffice it to say that Voltaire, who wrote 52 volumes of works, which, in addition to fiction, included works on aesthetics, history and philosophy, had a monument erected during his lifetime. It is no coincidence that the period of Enlightenment itself in some countries was called after philosophers. In France, for example, this period was called the century of Voltaire, in Germany - the century of Kant.

If the 17th century was the century of scientific discoveries, then the 18th century. became the century of public acquaintance with science. The Age of Enlightenment gave birth to a new type of consumer of intellectual products - the mass reader. This time was characterized by huge circulations of newspapers, magazines and books (1.5 million volumes of the works of Voltaire (1694 – 1778) alone and about 1 million volumes of the works of J.-J. Rousseau (1712 – 1778) were published. Interest in scientific and fiction is so great that in England, for example, libraries were opened even by societies of hairdressers.

A new phenomenon of the era was the publication of dictionaries: when the edition of the English Universal Dictionary appeared in the Paris Library, a queue lined up at its doors every morning. The answer to this intellectual need of society was the publication of the French “Encyclopedia, or Explanatory Dictionary of Sciences, Arts or Crafts” - a multi-volume publication on all branches of human knowledge, ed. J. d'Alembert and D. Diderot (1713 – 1784). For the period 1751 - 1780 35 volumes were published, in the creation of which the most outstanding scientists of that time took part.

Thanks to the achievements of natural sciences, the idea arose that the time of miracles and mysteries was over, that all the secrets of the universe had been revealed, and that the Universe and society obeyed logical laws accessible to the human mind.

5. Historical optimism.

The Age of Enlightenment can rightly be called the “golden age of utopia.” The Enlightenment primarily included the belief in the possibility of changing people for the better by “rationally” transforming political and social foundations.

Back at the end of the 17th century, in 1684, P. Bayle’s “Dictionary” was published - the world’s first “reference book of errors and misconceptions,” where well-known religious theses were criticized, and where a kind of declaration of a new culture sounds: “We live in times that will continue to become more and more enlightened, while previous centuries will become, by contrast, more and more dark.”

The idea of progress, which took hold in this era, is also associated with historical optimism, according to which man and his history progress from simple to complex thanks to the accumulation of knowledge.

A reference point for the creators of utopias in the 18th century. served as the “natural” or “natural” state of society, not aware of private property and oppression, division into classes, not drowning in luxury and not burdened with poverty, not affected by vices, living in accordance with reason, and not according to “artificial” laws. It was an exclusively fictitious, speculative type of society, which some philosophers contrasted with modern European civilization (J.-J. Rousseau).

6. Absolutization of education.

The Age of Enlightenment put forward a special understanding of education, called the “blank slate” theory (“tabula rasa”) (D. Locke), according to which a person is born absolutely “pure”, without any positive or negative predispositions, and only the educational system shapes his personality. The Enlightenment saw the task of education as creating favorable conditions and breaking with traditions, because the new person must be free, first of all, from religious postulates.

Despite the naivety of such views of the enlighteners, it should be noted that the enlighteners were the first to reject the dogma of “original sin” and the original depravity of man.

Associated with this is a new understanding of nature. For educators, nature is a reasonable, natural beginning. Everything that was created by nature was declared virtuous and natural: natural man, natural law, natural laws... Nature was represented as the mother of man, and all people, as her children, were equal and separated from God.

The embodiment of the educational understanding of nature and man was the novel by D. Defoe (1660 - 1731) “Robinson Crusoe,” which emphasized the ideas of the creative activity of man living according to natural laws.

7. Secular character.

The era of enlightenment made earthly life one of the main values of man. One of the key theses of the era may be the words of Voltaire: “Everything is for the best in this best of worlds.”

Life was perceived as a holiday, and “to be” was now understood as “to be happy.” "Enlightened Epicureanism" becomes the new popular philosophy. In his work “On Pleasures,” Saint-Evremond said: “We should forget the times when one had to be harsh in order to be virtuous... Delicate people call pleasure what rude and uncouth people call vice.”

Sensuality and erotic energy were declared the “new virtue.” Diderot, loudly calling on art to condemn vices, sometimes mentions that “vice is perhaps more beautiful than virtue.”

“The love of pleasure is reasonable and natural,” LaChapelle declared in his “Dialogues on Pleasures and Passions,” one of the central books of the 18th century. became Fontenelle's book "On Happiness". It provides a philosophical basis for new views: since absolute happiness is unattainable, one must maintain the illusion of happiness (independence, leisure, pleasant conversation, reading, music, entertainment and pleasures of various kinds).

These ideas were best reflected by the art of the 18th century, and especially by such a movement as Rococo.

8. Anti-feudal character.

The bearers of the ideas of the Enlightenment were mainly representatives of the 3rd estate: scientists and writers, writers, teachers, lawyers and doctors. One of the main demands of the era was the fight against hereditary privileges and class restrictions: it was believed that people come into the world equal, with their own needs and interests, which can be satisfied by establishing reasonable and fair forms of human society.

The minds of the enlighteners were excited by the idea of equality not only before God, but also before the laws and before other people. The imperfection of the existing social system is grotesquely ridiculed in the work of the English writer D. Swift (1667-1745) “Gulliver's Travels”.

The founder of educational ideas was the English philosopher D. Locke (1632 - 1704), who developed the idea of natural human rights (life, freedom and property were declared fundamental and inalienable rights). Based on this understanding of rights, a new understanding of the state arose: the state was created by agreement of free people and must protect a person and his property.

The idea of equality of all people before the law is a characteristic feature of the Enlightenment: “The natural rights of the individual, which belong to everyone by birth, are given by God to everyone and do not depend on nationality, religion and origin.”

9. The idea of “Enlightened absolutism”.

The enlighteners were not, of course, so naive as to think about the reality of education and re-education of every person. And with all their commitment to constitutional order, they could not help but see that real power was concentrated in the hands of monarchs.

The consequence of this situation was a new idea of the enlighteners, according to which it was not the union of the monarch and the church that should flourish in society, but the union of the monarch and philosophers. Indeed, the popularity of educational ideas was so great that they became increasingly famous not only in aristocratic salons, but also at royal courts.

XVIII century for many countries it became the century of enlightened monarchs: in Germany - Frederick II, in Sweden - Gustav III, in Russia - Catherine II, in Austria - Joseph II of Austria, in Spain, Portugal, Denmark - ministers who shared educational views and carried out reforms. Only two large European countries violated this pattern: England, because it was already a constitutional monarchy and France, in which there were no reforming kings, for which it paid with the Great French Revolution.

National characteristics of the Age of Enlightenment

England is the country of the first bourgeois revolution, where the bourgeoisie and liberal intelligentsia by the 18th century. have already gained political power. Therefore, the uniqueness of the English Enlightenment is its emergence not before, but after the bourgeois revolution.

In France, based on the ideas of the English F. Bacon and D. Locke, educational ideas developed very quickly, and from the second half of the 18th century. it became a pan-European center of Enlightenment. The specificity of the French version of the Enlightenment was its “categoricalness” and “intransigence.” The total criticism of religion is explained by the fact that there was no Reformation in France, and the sharp criticism of the feudal order is explained by the political backwardness and lack of rights of the bourgeoisie. The “elder” generation of French enlighteners were F. Voltaire, C. Montesquieu (1689 – 1755), the “younger” generation included D. Diderot, C.-A. Helvetius (1715 – 1771), P.-A. Holbach (1723 – 1789).

The German Enlightenment almost did not touch upon political (Germany was not a unified state) and religious issues (the Reformation resolved them). It dealt with the problems of spiritual life, philosophy and literature (I. Kant (1724 - 1804), who formulated the central principle of ethics based on the concept of duty, G. Lessing (1729 - 1781), poets I. Goethe and F. Schiller).

In Italy, enlightenment ideas manifested themselves only in the anti-clerical sentiments of the intelligentsia.

In Spain, a small group of ministers opposed to church and court tried to implement Enlightenment ideas in public policy, without theoretical justification.